Managing substance use disorders with ‘empathy and love’

History, politics and morals converge in the field of harm reduction, which researchers say is about much more than telling people how to safely use drugs.

The goal of harm reduction is to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug use, which people who work in the field say is accomplished through compassion, empathy and love.

Harm reduction. On the surface, the two words represent an idea that most people would support – lowering the level of harm an individual experiences. But in the world of substance use disorders, government legislation and societal conventions, the policy and practice of harm reduction is highly controversial, with little middle ground.

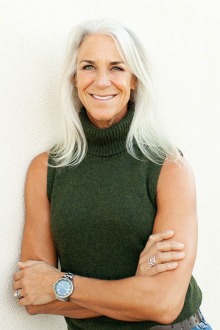

Beth Meyerson, PhD, runs the Harm Reduction Research Lab in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson and serves as policy director for the Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction at UArizona Health Sciences.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration defines harm reduction as “an evidence-based approach that is critical to engaging with people who use drugs and equipping them with life-saving tools and information to create positive change in their lives and potentially save their lives.”

It is providing people who inject drugs with clean needles. It is increasing access to opioid overdose reversal medications such as naloxone. It is providing counseling and education on where to find treatment facilities.

But it is so much more.

“When I teach about harm reduction, I teach that harm reduction is a moving, living, organic concept,” said Beth Meyerson, PhD, policy director for the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction and director of the Harm Reduction Research Lab in the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Family and Community Medicine. “We understand it best when we are working with the communities that are harmed and providing them space to teach us what harm and harm reduction really means.

“For example, if harm reduction was only about syringe access, we would have totally missed what's going on now, with people smoking ‘blues’ who can’t get sterile smoking equipment. We would also miss the chance to work toward expunging drug possession charges so that people can enter the workforce without inhibition,” Meyerson added. “So, when we think about harm reduction, it really is about working with people at the center of the nexus of harm, listening and then learning what harm means.”

Humans and drugs: a brief history

Smoking “blues,” counterfeit oxycontin pills laced with fentanyl, is one of the ways people consume drugs today, but drug use in and of itself is far from a modern invention. The first direct evidence of ancient drug use was identified by researchers who chemically analyzed human hair preserved in a burial cave in Menorca, Spain. The analysis found alkaloids of three plant-based psychoactive substances, providing evidence that people some 3,000 years ago used drugs, perhaps as part of a ritualistic ceremony.

Indirect evidence of human drug use dates back even further. Research shows that roughly 13,000 years ago, people in southeast Asia consumed betel nut, a highly addictive stimulant. Cocaine was taken by people in the Andes 7,000 years ago, and Australian aborigines have been using nicotine from indigenous plants for 40,000 years or more.

Scientists have postulated multiple theories about how humankind went from utilizing drugs for food, medicine and rituals to experiencing substance use disorders – or rather, using so chaotically that their lives became unstable. The shift came at a high cost: in the United States, more than 760,000 people have died from a drug overdose since 1999, and nearly 75% of drug overdose deaths in 2020 involved an opioid, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Suffice to say the opioid epidemic looks nothing like anything seen before in history. Still, that does not make harm reduction an innocuous answer.

“The health outcomes of substance use aren’t linear connections, they are also created and mediated by our socialized views about drugs themselves and the people who use them,” Meyerson said.

Breaking down stigmas and stereotypes

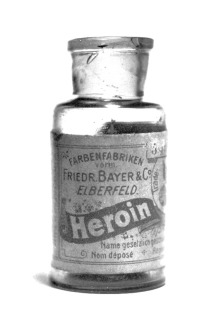

In the early 1900s, there was little government oversight over drug use, which was considered a personal or medical matter. That changed with the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914, which represented the first governmental regulation of narcotic sales.

Narcotics including heroin were used as medicine and sold by pharmaceutical companies such as Friedr. Bayer & Co., precursor of the pharmaceutical giant Bayer Group. (Mpv_51, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Harrison Act was intended to combat narcotic trafficking. It required anyone who sold or distributed narcotics, including doctors, to register with the government and pay a tax. But it did not address whether a doctor could prescribe long-term maintenance doses of narcotics to keep people who were addicted to the drugs comfortable. The issue went to court, and in 1919, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against allowing doctors to prescribe maintenance doses of narcotics, effectively creating the first anti-maintenance narcotics policy.

The late 1800s and early 1900s were a pivotal time in harm reduction history, shaped by the “the demonization of the psychoactive drugs associated with stigmatized racial/ethnic minority groups,” according to a 2017 commentary published in the Harm Reduction Journal, Don Des Jarlais, PhD, director of research at the Mount Sinai Health System’s Baron Edmond de Rothschild Chemical Dependency Institute.

Policies such as the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which banned Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S., resulted in part from the medical community’s belief that “the Chinese opium smoking habit threatened the moral system of the country,” according to a 2000 article by historian Diana Ahmad published in the journal American Nineteenth Century History.

Harm reduction can include providing needle exchange kits to people who inject drugs. Syringe services programs reduce the transmission of infectious diseases including HIV, hepatitis B and indective endocarditis. (Todd Huffman, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

The demonization of specific drugs, including opium, cocaine and marijuana, did not prevent the use of the drugs, but it did result in a fear of the drug itself. As a result, people who used drugs were stigmatized and stereotyped. Criminal action or abstinence became the only acceptable policies for drug use, which was turned into a moral issue rather than a health issue.

Meyerson uses the human papillomavirus vaccine as a modern example of a moral policy issue. HPV, a common sexually transmitted infection, is the cause of cervical cancer. The vaccine reduces that risk, especially in if given to people who were not yet sexually active. Meyerson worked with state legislators in Indiana to make the vaccine available to young children, but faced significant resistance from some people who believed sexual abstinence was the only appropriate policy.

“It's not easy to talk to parents about kids and sex. We were framing it as a cancer prevention that kids need access to before their sexual debut, but all we heard was, ‘Well, they just shouldn't have sex,’” Meyerson related. “If they had sex, the health outcome was causal and contracting HPV or cancer was somehow justified.

“This where we are with harm reduction. The behavior of drug use is judged. And if the behavior is changeable, we don't want to protect anyone at all.”

Meyerson is hoping to change that.

As an approach, harm reduction emphasizes kindness and autonomy in the engagement of people who use drugs.

Improving treatment and empowering patients

The goals of the Harm Reduction Research Lab are to improve the health of people who use drugs through collaborative research to reduce opioid overdose death and bloodborne illnesses such as HIV and hepatitis C.

The lab team is composed of faculty at seven universities across the U.S. and one in Australia who work closely with the Drug Policy and Research Advocacy Board, which was originally formed as an advisory council for a study that examined the impact of policies governing access to medication for opioid use disorder, or MOUD. The collaboration was so successful that the group was incorporated into the lab permanently.

The University of Arizona has hosted several opioid overdose prevention events, where students learn how to administer life-saving naloxone and receive information about harm reduction and drug use.

The Drug Policy and Research Advocacy Board is a statewide, transdisciplinary group of people who guide the research of the Harm Reduction Research Lab. Members include state government officials, health insurance providers, MOUD providers, people who use drugs regardless of if they are in recovery, people engaged in methadone or buprenorphine treatment, and harm reduction organizations. Their engagement informs decisions, guides the lab’s research and helps define what harm is from multiple perspectives.

Of the lab’s goals, Meyerson is particularly passionate about one specific harm reduction strategy: improving access to evidence-based, standard-of-care treatments for opioid use disorder, including methadone, buprenorphine, naloxone and naltrexone. She is using a $1 million grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a division of the National Institutes of Health, to lead the study “Methadone Patient Access to Collaborative Treatment,” or MPACT. Over the next two years, the research team will collaboratively develop and test a patient-empowered, trauma-informed methadone treatment protocol in Arizona.

“That could reduce opioid overdose deaths by 60%, and some studies say 80%. That’s life-changing when we think about the fact that one person dies every five minutes from an opioid overdose in the United States,” Meyerson said.

“Harm reduction is often talked about in terms of drug use or things that mitigate the negative outcomes of drug use. But when I think about harm reduction, really, it’s all about empathy and love. That’s what harm reduction is.”

Our Experts

Beth Meyerson, PhD

Policy Director, Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction, UArizona Health Sciences

Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson

Director, Harm Reduction Research Lab, Department of Family and Community Medicine, UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson

Related Stories

Contact

Stacy Pigott

UArizona Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-621-7239 office | 520-539-4152 cell, spigott@arizona.edu