Joining Forces in the Fight Against Valley Fever

A new collaboration is combining the strengths of Arizona’s three public universities to advance Valley fever research and clinical care.

The doctors didn’t know what was wrong with Paul Ness. His headaches led them to believe he had temporal arteritis. When he started coughing up blood, they thought he had pneumonia. When the treatments for that diagnosis failed to work, a biopsy revealed the true cause – Valley fever.

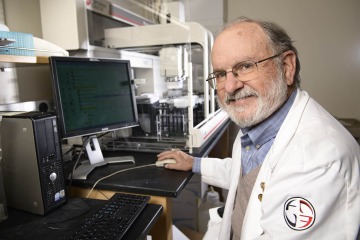

Paul Ness, who has been diagnosed with meningitis caused by Valley fever, and John Galgiani, MD, discuss the medication Ness will be taking as a participant in a clinical trial that is testing a new treatment for Valley fever.

Ness is one of an estimated 40,000 Arizonans who contract Valley fever every year. In most cases, the body's immune response leads to a complete recovery within six months. That wasn’t the case for Ness. Despite being treated with various anti-fungal medications, he kept getting sick.

“The current drugs are quite useful, but they have limitations,” said John Galgiani, MD, director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson. “One of the major limitations of available treatments is they don't cure this disease. Another is they don't always work. And for this patient, both are true.”

Eventually, a spinal tap confirmed that the headaches plaguing Ness were not caused by temporal arteritis but by meningitis, the most serious and lethal complication of Valley fever. Ness is currently enrolled in a clinical trial at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, where researchers are testing a new drug to treat Valley fever.

Dr. Galgiani, director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, has been studying the fungal disease for more than four decades.

“For him, it is an important opportunity because otherwise he would not have alternatives to help control his disease,” said Dr. Galgiani, professor of medicine and member of the BIO5 Institute. “If we could find drugs that would cure this disease, we'd be enormously ahead. I think this disease needs those kinds of opportunities.”

Thanks to the new Valley Fever Collaborative, more opportunities are on the horizon. The state-wide network connects experts at UArizona Health Sciences, Arizona State University and Northern Arizona University to facilitate collaboration and solve what is an important public health and economic problem in the Southwest.

Creating the Valley Fever Collaborative

The foundation of the Valley Fever Collaborative rests firmly on decades of successful Valley fever research each university brings to the table.

“The last couple of years have really been a tipping point, in many ways, for recognition of Valley fever as an important problem to address,” Dr. Galgiani said. “This is a very good time to grow a collaboration, in part because the strengths are growing at all three schools.”

The goals of the Valley Fever Collaborative include:

- Providing the public with accurate information about the risks of Valley fever to increase community understanding of the disease.

- Providing broad-based medical education about Valley fever to help doctors diagnose and manage Valley fever correctly.

- Developing precise diagnostics, including rapid and sensitive diagnostic tests, tests to detect the fungus in the soil, nonsurgical tests to distinguish Valley fever from lung cancer, and tests to determine the risk of serious Valley fever complications among people who are not immune.

- Finding drugs that can cure Valley fever, rather than simply suppress the fungus.

- Developing preventative measures, including canine and human vaccines, and methods to find and remove the fungus from the soil.

“The three universities are coming together to leverage our individual expertise, infrastructure and strengths,” said Paul Keim, PhD, Regents Professor of Biology and executive director of the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute at Northern Arizona University. “At NAU we've been interested in dangerous pathogens for over 30 years, and we are particularly good at pathogen genomics.”

Paul Keim, PhD, Regents Professor of Biology at Northern Arizona University, developed a genetics-based diagnostic test for Valley fever by searching the Coccidioides genome for highly repeated DNA sequences, identifying a novel repeated DNA sequence and converting it to a PCR test.

By studying the Coccidiosis genome, NAU researchers were able to develop one of the few FDA-approved tests to identify Valley fever in the soil. By identifying where Valley fever cases originate, researchers can inform decisions to reduce public health risk.

Other research topics at NAU include studying the biology of the fungus within the host. Gaining a clearer understanding of how the fungus behaves may give researchers insight into why Valley fever disproportionately affects people of color.

“What we know from the epidemiology over the last century is that people of color, especially African American and Filipino, have had an increasingly disproportionate amount of problems with this disease compared to other ancestries,” Dr. Galgiani said. “That being the case, any advances we make with this disease will disproportionately benefit people of color.”

At ASU, researchers have focused on developing better diagnostic tests for Valley fever. Currently, almost all diagnostics for Valley fever are based on antibodies to the disease, and false-negative rates can be as high as 50-70%.

Valley fever presents a significant burden on Arizona’s economy, costing an estimated $736 million in 2019 alone.

“There have been a number of different ASU researchers and groups that have looked at diagnostic technologies and diagnostic processes for the disease, and I think that's probably where we'll be able to contribute most strongly in this in this effort,” said Neal Woodbury, PhD, vice president for research and chief science and technology officer for ASU’s Knowledge Enterprise.

Neal Woodbury, PhD, is the chief science and technology officer at Arizona State University, where researchers are focusing on diagnostic capabilities, the immune response to Valley fever, and the physical transmission properties of the fungus in the air and in the body.

ASU researchers are approaching the problem from multiple angles. One research path is focused on developing a test that would detect microscopic parts of the fungus itself, rather than relying on antibodies.

Another area of focus is an innovative new technique known as “immunosignaturing,” which can produce a detailed profile of system-wide immune activity from a small droplet of blood and potentially offers much higher resolution and sensitivity to disease than current tests.

“It’s a tricky diagnosis. We've had a couple of different groups that have come up with serology tests that look pretty good. But we need to ask the question, ‘How do we move it into practice?’” Dr. Woodbury said. “I think through the larger effort of the Valley Fever Collaborative connecting all of us, we have a much higher probability of moving these things forward and making them clinically useful.”

When it comes to clinical application, UArizona Health Sciences is contributing the resources of one of the leading academic medical centers in the Southwest. Dr. Galgiani and others in the Valley Fever Center for Excellence have spent decades educating doctors, treating patients and conducting research.

People and dogs can get Valley fever by inhaling airborne spores of the fungus coccidioides, which are carried in dust particles from the soil by the wind when the desert soil is disturbed. UArizona Health Sciences researchers are leading the development of a potential canine vaccine, which may pave the way for a human vaccine.

One of their research primary goals has been the development of a vaccine for Valley fever. They are close – a recently concluded study showed that a potential vaccine candidate protected dogs from getting Valley fever after trial infection. Eventually, the hope is that a canine vaccine will create a pathway for developing a human vaccine.

“There are so many things that could be done to make this disease much less of a problem for people,” Dr. Galgiani said.

People like Paul Ness, who will need lifelong treatment to keep the disease at bay. For him, and many others like him, the Valley fever research taking place in Arizona could be lifesaving.

“I'm starting the second phase of treatment,” Ness said before his most recent visit with Dr. Galgiani. “The neurologist at the Mayo Clinic said, ‘I think we’re gaining on it,’ and I do feel a little better than I have in the past. But it's a slow process.”

If Drs. Galgiani, Woodbury and Keim have their way, the Valley Fever Collaborative will change that by using collaboration to accelerate innovation.

“The more people who want to work on Valley fever,” Dr. Galgiani said, “the more chance we have of faster solutions.”

Our Experts

John Galgiani, MD

520-626-4968

spherule@email.arizona.edu

Contact

Stacy Pigott

520-621-7239

spigott@arizona.edu