Persevering on the path to becoming a physician

Medical student Taylor Hoffman’s life with Type 1 diabetes fueled a passion to help others who live with autoimmune disorders and chronic health conditions.

Taylor Hoffman, a second-year student at the College of Medicine – Phoenix, believes that her lived experienced managing Type 1 diabetes and multiple autoimmune disorders will make her a better physician.

Taylor Hoffman, a second-year student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, received a UArizona Health Sciences Primary Care Physician Scholarship in 2022.

Consequently, Hoffman’s parents participated in a trial that searched for genetic mutations associated with Type 1 diabetes. Her mother, who was adopted as a baby, even petitioned the court for her birth family’s medical history.

“Results showed my diagnosis wasn’t due to any known genetic mutations. I was, in fact, a one-in-a-million case,” Hoffman said. “There was no family history of diabetes, no predisposing factors and no known scientific explanation for my condition.”

As she got older, Hoffman came to see diabetes as a way for her to help people dealing with similar circumstances, and her experiences with doctors – both good and bad – fueled a desire to become a compassionate, caring physician. She is now a second-year medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix.

“When I become a doctor, my job will be to treat my patients and their families as teammates striving toward the same goals, and I will support them in any way I can, all the while adapting to where they are on their journey,” said Hoffman, who received a UArizona Health Sciences Primary Care Physician Scholarship in 2022.

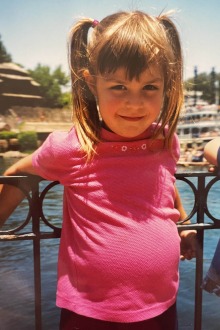

On a trip to Disneyland when she was 5, Hoffman’s family used park services that allowed them to store insulin in a refrigerator in case her insulin pump failed and leave instructions on how to treat her diabetes in the event she was separated from her parents.

Living with diabetes, and more

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases describes diabetes as “a disease that occurs when your blood glucose, also called blood sugar, is too high.”

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the body’s immune system attacks and destroys insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Without insulin, glucose is unable to get into the body’s cells and blood glucose rises above normal. People with Type 1 diabetes need to take insulin every day to stay alive.

After hearing their young daughter had Type 1 diabetes, Hoffman’s parents learned how to diligently manage her disease to the best of their abilities and taught her to do the same as she grew up. Meanwhile, doctors frequently reassured them a cure was coming.

“Hang in there. It’s only five years away,” Hoffman remembers being told throughout her childhood.

Decades later, there is still not a cure for Type 1 diabetes, and Hoffman’s diagnoses now include other chronic diseases and associated autoimmune disorders.

In 2001, when she was 4 years old, Hoffman was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. Doctors later changed that diagnosis to celiac disease, an illness caused by an immune reaction to gluten, a protein found in wheat. Eight years later, she was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism, an autoimmune disorder that affects the thyroid gland.

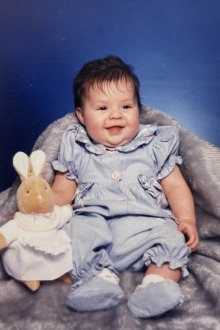

Though she was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at 18 months, Hoffman started to have recurring health issues, most often ear infections with no known explicit cause, much earlier. She says her family now knows these recurrent infections were caused by her dysfunctional immune system.

“By that time, I was old enough to recognize that these diagnoses were not random occurrences,” Hoffman said.

Praying for a breakthrough

Hoffman started doing her own research and came across a published paper about an observational study in Scandinavia that suggested a genetic link between Type 1 diabetes, celiac disease and Hashimoto’s.

“I felt a sense of relief knowing that there was data validating what my family and I had suspected all along,” Hoffman said. “I couldn’t stop myself from praying that research like this would lead to a scientific breakthrough that would cure all my conditions with one injection and be the solution we had been waiting for.

“Diabetes is a disease that does not behave the same way two days in a row, even when you do the same things every day and sticking to the same routine. It fluctuates like the wind, and despite having a forecast, like my continuous glucose monitor, it can be hard to predict,” Hoffman said. “It has been my greatest teacher while being my biggest adversary. Education and advocacy have become a full-time job in both my personal and professional lives, as I am sure is true for many others.”

(From left) Hoffman and Raquel Moore, also a student at the College of Medicine – Phoenix, were the only two medical students approved to be staff members with the training to treat over 100 kids with Type 1 diabetes and other accompanying chronic conditions at Camp AZDA in Prescott, Arizona, last year. The camp is run by the American Diabetes Association.

Not everyone shared Hoffman’s optimism. When she was an undergraduate, she met with a career advisor to help her plot a path to medical school. She was asked what made her a unique candidate, and Hoffman outlined her own patient history. To Hoffman’s astonishment, the advisor saw these conditions as obstacles that would be difficult to overcome and encouraged Hoffman to think about different career pursuits.

Undeterred, Hoffman continued to chase her goals, but not without another setback. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis while completing the Pathway Scholars Program at the College of Medicine – Phoenix. The program is designed for students who have experienced unique or greater-than-average challenges in preparing to become competitive medical school applicants.

“Ultimately, I hope my perspective shows people that anything is possible with discipline, and that just because you have a disease does not mean you are destined to become a stereotype or statistic,” Hoffman said.

As her medical school studies continue, Hoffman is as determined as ever to use her lived experiences as a benefit to help others.

She believes the medical field is at a crossroads, where the rapid development of precision medicine treatments may soon provide the therapeutics and cures patients have waited a lifetime for. To that end, she is looking forward to seeing the UArizona Health Sciences Center for Advanced Molecular and Immunological Therapies develop at the Phoenix Bioscience Core. CAMI researchers will focus on unraveling the complexities of the immunology of cancers, infectious diseases and autoimmune conditions, potentially giving families like the Hoffmans answers to questions to they have asked for years.

“I cannot wait to see how patient care evolves over my career because of innovations developed by CAMI,” Hoffman said. “I know there will come a day when we won’t say, ‘Just hang in there,’ and instead will say, ‘The wait is over, today is your last day with diabetes.’”

Contact

Blair Willis

UArizona Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-419-2979, bmw23@arizona.edu